Here are some of the stories...

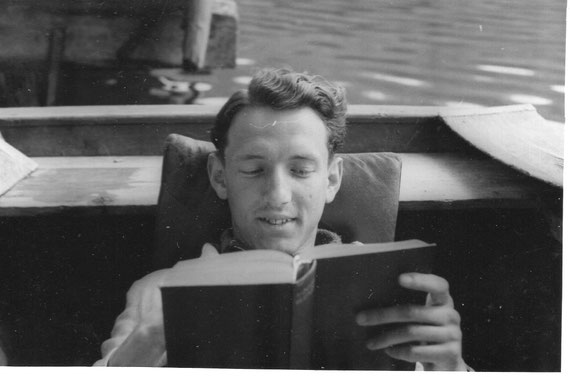

Student Dimitri R. Stein, Neuglobsow, Stechlinsee (c) David Stein

Dr. Dimitri R. Stein, who was denied his Dr.-Ing. at the TH Berlin because he was Jewish, and his father, Roman I. Stein who was murdered in Auschwitz, are remembered at the Technical University Berlin with the help of photographs, letters and a video recording.

In Terijoki, Finlandia, after their escape from USSR, June 1920 (c) David Stein

Dimitri R. Stein (1920-2018) was born into a liberal Jewish-intellectual family in Petrograd.

In the summer of 1920, the family fled from St Petersburg to Finland to escape anti-Jewish violence after the Russian Revolution. They spent the following months in the Finnish town of Terijoki (now Zelenogorsk, Russia), which was overcrowded with thousands of Russian refugees.

Joseph Hessen, Dimitri’s grandfather,was a publisher, journalist and a member of the Russian Duma. He had close ties with the Berlin publisher Ullstein, who finally organised his entrance visa to Germany.

As a lawyer, Dimitri’s father Roman I. Stein was not able to obtain a work permit in Berlin. He worked as proof-reader and occasional contributor to Rul (Ruder), the Russian newspaper of his step-father Joseph Hessen in Berlin.

Ina Stein, Dimitri’s mother worked as a teacher at the German-Russian School (1931-1945) in Hohenstaufenstrasse (now Georg-von-Giesche-Schule, then Werner-von-Siemens-Gymnasium).

Although the every-day existence of the family was marked by the severe financial problems they faced, Dimitri retained memories of a good childhood. He spoke Russian with his parents at home, but spoke German outdoors and at school. The parents were atheists, and the young Dimitri did not feel Jewish. After primary school he went on to the Herder-Gymnasium at Reichskanzlerplatz (now Theodor-Heuss-Platz).

Roman and Ina Stein had neither the necessary contacts nor the funds to leave Germany. In 1936, Roman I. Stein emigrated alone to Paris, where some of his own family had already fled. Like the many other emigrants, he lodged in a small hotel, without employment and dependent on sparse support from Jewish aid organisations.

Dimitri and his mother were not allowed to send more than ten Reichsmark a month abroad. When Dimitri visited his father in Paris when he was 17-year-old 1937, he secretly took 300 Reichsmark in hard currency across the border.

Because he was classed as a foreigner by the Nazi regime, the stateless Dimitri did not have to provide proof of Arian status in 1938 when he enrolled at the Technical College Berlin (TH Berlin) to study electrical engineering.

His father had successfully talked him out of his wish to become a journalist – pointing to the collapse of his own career. With future emigration in mind, it was important to learn something practical, so that he would be able to find work everywhere.

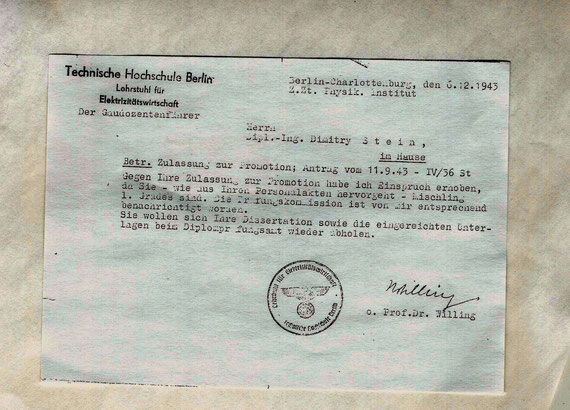

But his application to study for a doctorate at the TH Berlin was rejected in 1943 because of his Jewish origins.

Application rejected by the TH Berlin, December 6, 1943 (c) David Stein

Father and son saw each other for the last time in 1941.

As a stateless foreign Jew, Roman I. Stein was arrested in Paris in the summer of 1942 and on 14 September he was deported with Transport 32 from Drancy Internment Camp to Auschwitz-Birkenau. He was murdered directly after he arrived.

After the apartment in Prager Strasse had been searched on various occasions by the Gestapo and Dimitri had only been released after several days Gestapo imprisonment in Prinz-Albrecht Strasse with the help of a friend, he went into hiding in the southern part of Germany where he found refuge as a "war-worker" until the end of WW II.

After the death of his mother, Dimitri R. Stein emigrated to America in 1946. Helene Malyschew, his mother’s sister, provided surety for him. She had been in Swedish exile, where she looked after the daughter of the composer Rachmaninoff, and she had moved to New York with the Rachmaninoff family before the start of war.

In New York Dimitri met the Russian interpreter Sophie Baschkin, who had also fled from Berlin. He got by with part-time jobs until he was appointed as a teacher at Fargo University in North Dakota.

Sophie Baschkin and Dimitri R. Stein were married in June 1948. Because Sophie worked for the UN, Dimitri returned to New York and set up his own business, specialising in cabling.

At the age of 88 years, Dimitri R. Stein was rehabilitated by the Technical University Berlin and after an examination he was awarded his doctorate.

On 27 October 2018 Dr. Dimitri R. Stein passed away at his home in Watermill/NY. He is followed by three sons, seven grandchildren and a great-grandson.

Technische Universität Berlin, Straße des 17. Juni 153, main building, atrium gallery (Lichthof) on the 2nd floor, Berlin-Charlottenburg

10:30am - 12 noon | Exhibition and video (German/English)

Dr. Daniel T. Stein (Scarsdale/NY), son of Dr. Dimitri R. Stein, will be present.

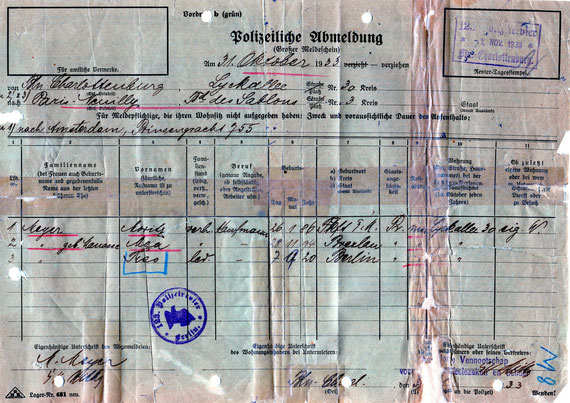

Berlin-Charlottenburg, Lyckallee 30

Jo Glanville at the terrace of Lyckallee 30, 2018 (c) Jani Pietsch

Méa, Moritz and Theo Meyer lived at 30 Lyckallee for just two years. They commissioned the architect Fritz Marcus to build the house for them - a state-of-the-art, modernist home. Their niece Pamela Glanville, the daughter of Méa’s brother Fritz Manasse, spent some of her childhood at the house. Thanks to Jani Pietsch’s dedicated research, Pamela’s daughter Jo Glanville was able to locate the house and to reconstruct some of their last days from the reparations files. We are grateful to Herr Schele for allowing the house to be opened to the public for Denk Mal Am Ort.

The family fled to Paris in October 1933. Moritz and Theo were immediately interned by the French when war broke out. They lived for a period under fake identities in Vichy France.

Polizeiliche Abmeldung für Moritz, Méa und Theodor Meyer, Berlin, 21. Oktober 1933

(c) Landesverwaltungsamt Berlin

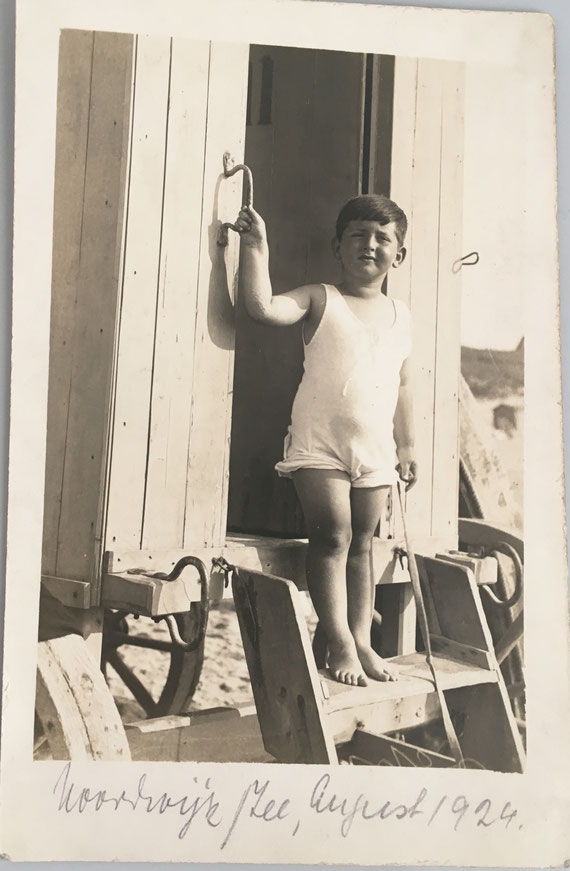

Méa was the only member of her immediate family to survive. Her son Theo was murdered in Auschwitz at the age of 23; her husband Moritz died from ill health after being held in internment camps in France. Méa managed to escape to Switzerland. She applied to the German government for compensation over a period of more than ten years. She spent the rest of her life in Paris.

Theo Meyer, August 1924 (c) Jo Glanville

The documents that will be on display on 5 May at Lyckallee 30 will give an insight into the bureaucracy of reparations: the number of categories in which claims could be made, as well as the sheer extent of witness statements and documentation that was required in order to make a claim. Méa had to track down proof of every stage in their lives and their flight from the Nazis: from her son Theo’s university certificate to evidence of the internment camps in which her husband was held. Perhaps one of the most chilling details is Méa’s claim for Theo’s imprisonment at Auschwitz: 5DM for each day that he was held. The reparations file also reveals previously unknown information about the family’s experiences during the war, including details of Theo’s arrest and Moritz’s death.

The documents include the administration of Theo’s transport from Drancy transit camp to Auschwitz, from the Centre de Documentation Juive Contemporaine in Paris: the telegrams sent by the Nazis ordering the transport and the instructions to prisoners for leaving Drancy. It is an insight into the methodical detail with which every transport was planned and executed.

Fritz Marcus, the architect who built 30 Lyckallee, also left Germany in 1933. He found refuge initially in Spain and then went to London, where he taught at the Central School of Arts and Crafts. He was part of a circle of German-Jewish refugee architects that included Ernst Freud, son of Sigmund Freud.

In memory of Méa, Moritz and Theo Meyer, Pamela Glanville and Fritz Marcus.

Lyckallee 30 | Berlin-Charlottenburg

Sunday 5th May | 1 pm | Exhibition and talk (Jo Glanville, English)

Berlin-Spandau, Am Wall 3

commemorating the Sternberg family (c) Doris Hinzen-Roehrig

With text passages and her own illustrations, Doris Hinzen-Roehrig recalls Spandau residents who were persecuted.

On her walking tour the visual artist also focuses on the Sternberg family and their department store Kaufhaus Sternberg - Das Haus der guten Qualität.

Walking tour | Sunday 5 May | 2:30pm - 4pm | meeting point: Commemoration plaque outside Spandau town hall | Am Wall 3 |

Berlin-Schöneberg, Torgauer Straße 24-25

Julius and Annedore Leber (c) Annedore and Julius Leber Archive

Julius Leber, a social democrat and Member of Parliament, was released from concentration camp in 1937, where he had been tortured for years. Friends found him work as a coal dealer in the Bruno Mayer Nachfolger coal business in Berlin-Schöneberg.

Julius Leber (c) Annedore and Julius Leber Archive

In 1944, Julius Leber was at the heart of the conspiracy against the Nazi regime. The coal dealer shop became a meeting point for the resistance; leading members of the Kreisau Circle and the military came here. After the war, Theodor Heuss, who later became the first Federal President, referred to it as a “conspirators’ hut”. The Gestapo arrested Leber at the coal dealer’s shortly before the 20 July assassination attempt. He was executed in Berlin-Plötzensee on 5 January 1945.

Annedore Leber (c) Annedore and Julius Leber Archive

Annedore Leber became the family breadwinner when her husband was arrested. She fought with tremendous energy for her husband’s freedom. When Julius Leber was rearrested, she too was taken to prison for a short time. Her children were forced to live with a new family. After her release, Annedore Leber was allowed to visit her husband several times in prison before his execution.

After 1945, Annedore Leber was passionately committed to keeping the resistance ideas alive. As an SPD politician, co-editor of the Telegraf newspaper close to the SPD and editor of her own magazine Mosaik, as an author, journalist and publisher, her chosen target groups were women and youth. She also rebuilt the coal dealer shop, which had been destroyed during the war and now included her publishing firm. Annedore Leber died in 1968 and was buried in the Waldfriedhof in Berlin-Zehlendorf.

There are plans to make the former coal dealer shop a place of learning and remembrance.

The former coal shop (c) Egon Zweigart

Torgauer Straße 24-25 | Berlin-Schöneberg

Saturday 4 May | 11am - 4pm | Open Air Exhibition

Berlin-Wilmersdorf, Nikolsburger Platz 4

Lily Katz, Hannover (c) Sylvia Paskin, London

Two Sisters

I was born in 1944 to refugee parents - my father Lothar was from Hanover and my mother Mimi from Vienna. We lived in a suburban London house in Wembley - beyond the door was austerity Britain, rationing, smog, the celebration of Empire Day at my school. But once through the front door you were in Middle Europe. The furniture my sophisticated grandmother Lily had brought from Berlin graced every room, on Saturday afternoons my mother baked Viennese pastries and cakes, Linzertorte, Apfelstrudel, Spitzbuben, Sachertorte with schlag. Every Sunday morning my father played chess and in the afternoon their friends came for tea- all continental - from Germany, Austria, Hungary and Czechoslovakia. I learned German by osmosis.

I remember too being frightened by a huge black Japanese cabinet, which stood ceiling high in our lounge. I imagined as a child that the menacing eagles, dragons and apes carved all over it were monsters who would come for me in my dreams. Inside the cabinet were other precious mysteries, Bohemian glass, Dresden china, monogrammed pink damask tablecloths, and the solid, warm curves of a sumptuous silver coffee set. The cabinet and its treasures, the Persian carpets, porcelain Meissen figurines, the paintings had all been the property of my grandmother Lily. My father was her only child from her first marriage to Leopold Sauer.

Lily Knips and her son Lothar, 3 years old (c) Sylvia Paskin, London

Lily was born in Hanover but lived in Berlin. She divorced her first husband and then married Franz Knips who was not Jewish. He died in 1935. At that time Lily lived in Berlin-Schöneberg in Freiherr-vom-Stein Strasse 8 but moved eventually to Wielandstrasse 30 in Berlin-Charlottenburg.

Lily Knips (left) c) Sylvia Paskin, London

Lily and Leopold had prescience and sent their son in 1933 to London to study at the London School of Economics. He subsequently met and married my mother and they made their life there.

As the Nazi’s took a grip on Germany and Europe Lily was in fear of her life. My father managed to get her out of Berlin in 1939 and she came to London.

In Berlin she had led a cultured and affluent life - now she was a refugee in a grey war–riven Britain, dislocated, living in a cold rented flat with lodgers, trying to come to terms with a totally new culture as did many others.

Llly suffered from depression. This was further exacerbated by an unhappy love affair. Whilst trying to escape from Berlin she had met a man, a non-Jew, Josef Jakobs who had a business providing passports to ‘help’ Jews get out of Germany. In the course of their dealings they had a love affair. He was eventually arrested by the Gestapo for creating these passports and pocketing the proceeds. Jakobs was sent to Sachsenhausen Concentration Camp. The only way he could get out was by agreeing to work for the Abwehr as a spy. He would be sent to England having been trained to send weather reports back from Britain to the Luftwaffe for their bombing raids. He was parachuted in January 1941 but he was immediately captured by the Home Guard as he broke his ankle on his descent. Lily’s name and address was on a piece of paper in his pocket. Did he intend to be a spy - did he intend to find Lily and implicate her in his espionage or simply get her to hide him? Imprisoned, interrogated, court-martialled, as he had been a former soldier, Jakobs was finally shot at the Tower of London. His fame rests on the fact he was last man ever to be executed there.

His death and her refugee life apparently proved too much for Lily and she became a casualty of the war by committing suicide by gas in 1943. She was 52 years old, an event from which my brilliant, troubled father never recovered.

Elsa Katz, Hannover (c) Sylvia Paskin, London

Lily had a sister, Elsa born in 1890. She married and divorced Alfons Majewski. She was a medical nurse but could not work as such being Jewish. She lived in Nikolsburger Platz 4 in Berlin-Wilmersdorf until 1940 in a building where 10 other Jewish people lived. She then was forced to move to a ‘Judenwohnung’ in Holsteinische Strasse 9 in Berlin-Schöneberg. Elsa was then deported on 13th June 1942 from Gleis 17 to Sobibor where she was murdered. The Nikolsburger Platz building was bombed and the site became the playground of the nearby Cecilien Schule. They have commemorated what happened to the Jewish occupants of the bombed building by laying 11 stolpersteine that encapsulate their fate. The school lays roses on the stolpersteine every year and lights candles…..

After Elsa died her landlord sold two sofas and two cushions for 10m, all that was left of her worldly goods but it was noted in 1943 in the Brandenburg state archives that ‘the emigrated Jew Majewski still had a property tax debt amounting to 90m….

My childhood home had beautiful objets d’art and fine furniture, and laughter was present when there were visitors but at other lonelier times it reflected the darkness, guilt and absences of the past. We were all haunted by the tragic family history of Lily and Elsa and also what happened to my mother’s parents in Vienna. There was no remedy. No exorcism could prevail.

Saturday 4 May | 2pm | Sylvia Paskin recalls two sisters at Cecilien-Schule | Nikolsburger Platz 5 | Berlin-Wilmersdorf

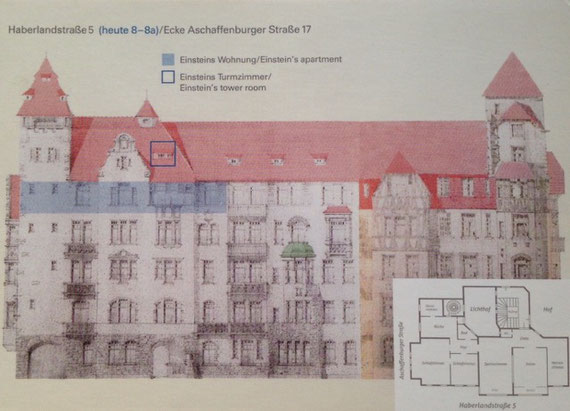

Berlin-Schöneberg, Haberlandstraße 8

(c) Gregorio Ortega Coto

Albert Einstein: I often think in music. I live my daydreams in music

Visitors will be able to see what Albert Einstein saw from his window (1917-1932) when Gregorio Ortega Coto opens his apartment on 4th floor to the public. Using documentary and artistic techniques, Gregorio Ortega Coto approaches this genius, visionary and musician with an electro-acoustic composition by Marion Fabian and Claudia Teschner on violin.

Saturday, 4 May | 1 - 3pm | Music, Documentation and Talk

Haberlandstr. 8 | Berlin-Schöneberg

Berlin-Charlottenburg, Mommsenstrasse 6

Bernhard Fiegel, his mother, and a lion baby (c)Naomi and Paul Fiegel, Sydney

The Fiegels were long-standing residents of Charlottenburg. For 25 years they lived in Mommsenstrasse, including at No. 6. Paul Fiegel was a wholesale seed merchant and owner of the firm founded by his father Benno. On 1 January 1919, Erna and Paul Fiegel welcomed their first and only child to the world – Bernhard.

Bernd, as he was known, started school in August 1925 at the 19th Gemeindeschule Charlottenburg, which was just round the corner in Bleibtreustrasse. Then until 1934 he attended the Kaiser Friedrich Gymnasium, which is now the European School Joan Miró.

Bernhard, with Anna and Elfriede, Berlin 1925 (c) Naomi and Paul Fiegel,

Sydney

We, Claudia Saam and Wolf Baumann, now live at Mommsenstrasse 6. Locating Naomi and Paul Fiegel in Sydney was a stroke of luck. And now we can see pictures of people that we had only been able to read about in the archives.

In 1936 – the year of the Olympic Games in Berlin - the Fiegels moved into a lovely 7-room apartment in Mommsenstrasse 6.

In a sworn statement to the Berlin Office for Compensation dated 27 January 1961, Erna Fiegel declared: "When we moved into the new apartment, we had all the fittings prepared by the architect Max Lewy, Berlin-Zehlendorf West, Beerenstrasse 20A; materials, carpets, and curtains were from the Gerson company, Berlin."

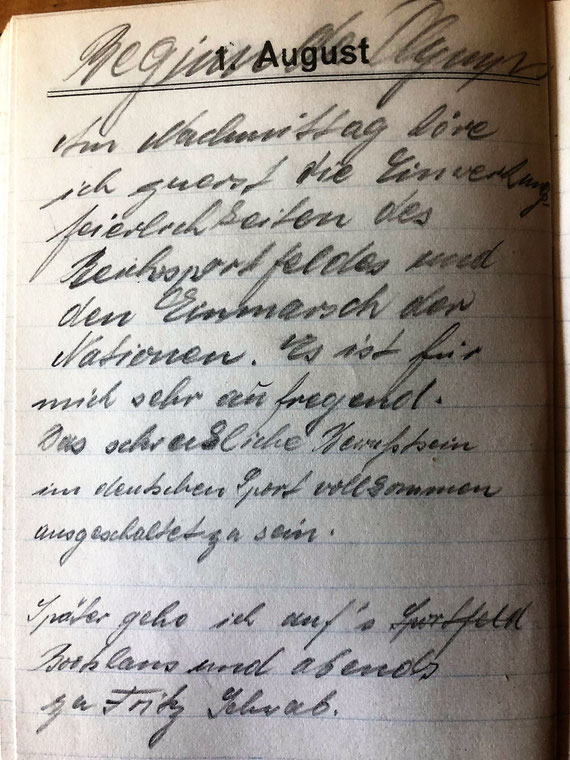

As a sports enthusiast, 17-year-old Bernd visited the Olympic Games in Berlin in 1936. In his diary he wrote on 1 August: "It is very emotional for me. The terrible awareness of being fully excluded from German sport."

Father and Son, Berlin 1935 (c) Naomi and Paul Fiegel, Sydney

Under pressure from the Nazi-authorities, Paul Fiegel was forced to sell his company on 1 July 1937, leaving him without any income. Following the anti-Jewish terror of the Kristallnacht in November 1938, the Fliegels decided they had to leave. In June 1938, Bernhard had moved to Gouda in the Netherlands, where he worked in the State Testing Institute for Ceramic Products. Erna and Paul Fiegel booked passage on the steamer DSS Slamat, which left Rotterdam on 10 June 1939 for Colombo. From there, they sailed with the SS Srathallan and arrived in Durban on 8 November 1939. Travelling by plane, Bernhard landed on the same day in Darwin. Reunited in Sydney, they began a new life. But things were not easy. Paul Fiegel worked as a labourer in order to feed the family.

(c) Naomi and Paul Fiegel, Sydney

On 1 October 1943, Bernhard Fiegel joined the Australian Army – an occasion for a photograph of mother and son. Five months after the end of the WW II, he became an Australian citizen and in 1946 he opened a ceramics business in Ashfield, Sydney. His mother helped out.

(c) Naomi and Paul Fiegel, Sydney

Bernhard Fiegel’s children Naomi and Paul are enthusiastic about DENK MAL AM ORT and are travelling to Berlin from Sydney in May to commemorate their father and grandparents – in the apartment of Wolf Baumann and Claudia Saam in Mommsenstrasse 6.

Tribute will also be paid to the Isaacsohn family and the Selten family. They were neighbours in Mommsenstrasse 6 until they were deported.

Abraham Isaacsohn, Judicial councillor (c) German Federal Bar Association

Judicial councillor Abraham Isaacsohn, known as Albert, his wife Anna and his son Franz Herbert moved into a six-room apartment in Mommsenstraße 6 in Charlottenburg in 1916, where they lived for 23 years. Abraham Isaacsohn worked at the Berlin Court of Appeal and the Prussian Ministry of Justice. He had been admitted as a lawyer to all three Berlin regional courts in 1893 and appointed a notary during the imperial period. His offices were located in Kaiser-Wilhelm-Straße 3. Abraham Isaacsohn is also said to have been active as a librettist under the name of Albert Knaus.

Abraham Isaacsohn was born in Brietzig (Pomerania) on 30 October 1866. He married Anna Fanny Reine Ranschoff, who was born on 4 December 1875 in Hanover. Their son Franz Herbert Isaacsohn was born on 31 January 1900 in Berlin. Franz Herbert later studied law and received his doctorate. He, too, was a lawyer at the Berlin Court of Appeal. In 1939 – prior to his emigration to New York – he lived in Knesebeckstraße 30.

In September 1939, Abraham and Anna Isaacsohn are located to a "Judenhaus" at Gervinusstrasse 24. Little is left to them. They have to pay RM50 per month for one room. They buy a place “for life” in a home in the Theresienstadt retirement ghetto for RM150 per month. For “transportation” they are obliged to seek out the Jewish old people's home in Grosse Hamburger Straße, now a collection camp. The head of the camp is Walter Dobberke, an assistant detective from the Jewish Department at the State Police headquarters in Berlin.

According to the files of the Chief Finance President, the Gestapo confiscated their assets to the advantage of the German Reich in accordance with the decree of 1 August 1942. This decree was delivered to the Isaacsohns while they were still alive at the collection camp with a notification by writ.

The collection camp was the last place they stayed in before the Gestapo took them to Grunewald railway station. On 17 August 1942, it was a Monday, they stood waiting at the goods station in Grunewald with 995 other Jewish citizens – including their neighbour Clara Lehmann – to be deported with the first large transport of the elderly (I/46) to Theresienstadt.

The names Abraham Isaacsohn with the identification card no. A 368020 and Anna Isaacsohn can be found on the transport list 147 with the transport numbers 0 6871 and 0 6872.

Abraham Isaacsohn survived 39 days in the camp and died on 25 September 1942. Having been called to Room no. 177 in Barrack IV, medical doctor Isa Herrmanns carried out a post mortem examination. She noted down heart failure (adynamia cordis) as the cause of death in the death certificate, which received the number 218. She fixed the time of death at 7:30 and named Dr. Helene Gutmann as the attending physician.

Anna Isaacsohn died on 6 November 1942, 41 days after her husband. Only 15 of the 997 people deported to Theresienstadt with the first transport of the elderly survived the ghetto.

On 24 April 2014, Stolpersteine were set into the pavement in front of Mommsenstraße 6 to commemorate Anna and Abraham Isaacsohn, and Margarete Bayer who lived with them.

On 4 and 5 May 2019, Claudia Saam and Dr. Wolf-Rüdiger Baumann open their apartment and recall the Isaacsohn family.

Mommsenstraße 6 | Berlin-Charlottenburg

Saturday and Sunday from 2-5pm

Berlin-Schöneberg, Apostel-Paulus-Str. 26

Johanna and Richard Landsberger, 1934 (c) Kurt Landsberger

When Kurt Landsberger sent this photograph in 2011, it was immediately clear to the current

tenant, Gabrielle Pfaff, on which floor the family lived on Apostel-Paulus-Str. 26 because each balcony was designed differently.

In 1933, the Landsberger family moved from

Crellestraße to Apostel-Paulus-Straße. The three children, Kurt, Inge and Gerd, initially attended schools nearby, but the worsening political situation left them with no option but to

attend a Jewish school. On 9 November 1938, the Gestapo arrested the children's father, Richard Landsberger, at his home. Due to his valid tourist visa for the USA, he was released from

Sachsenhausen concentration camp at the end of December 1939 on condition that he leave Germany immediately. He left for the USA in early January

1939. In February 1940, his wife Johanna followed with the children. Richard's brother, Franz, remained in the apartment. He informed his brother in New York that a short time later the

Gestapo had come to take 17-year-old Kurt, who by then was safe in New York. Franz Landsberger himself did not manage to escape. In September 1942, he was deported to Raasiku

in Estonia and murdered there.

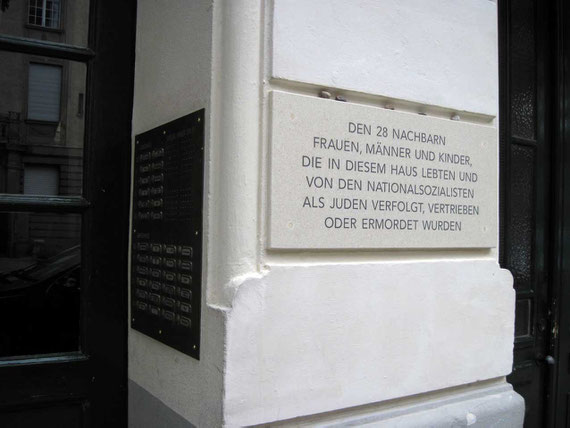

Commemorative plaque on Apostel-Paulus-Straße 26, 2012 (c) Gabrielle Pfaff

A plaque on the front of the house on Apostel-Paulus-Straße 26 commemorates the 28 former Jewish residents. Their names and other details are listed on a larger plaque in the hallway. Seven people (two adults and five children) escaped deportation.

The ceremonial unveiling of the two plaques took place in April 2012 in the presence of survivors and descendants, people from the neighbourhood, as well as district and

municipal politicians and representatives of various institutions.

The film documenting this event will be shown in the hallway on Sunday, 5 May between 1 and 3 p.m.

Berlin-Schöneberg, Rosenheimer Str. 40

(c) Claudia Samter, Buenos Aires

A photo from happier days in Berlin: Max and Else Simon, née Stargardt (left) with their daughter Helga and son-in-law Hugo Kaufmann (right). In between are Else’s sister Frida and her husband Willi Kastan.

Hugo Kaufmann managed to escape to the US in March 1941. Max Simon took his own life on 15 Oktober 1941. Else Simon, her daughter Helga and Helga’s four-year-old daughter Yvonne Luise were taken from Rosenheimer Straße 40 on 3 February 1943 and deported to Auschwitz.

Claudia Samter lives in Buenos Aires. She came across DENK MAL AM ORT last summer in an article by Susana Fernández Molina in the Spanish newspaper El País.

It took a few weeks and several emails for Claudia and us to realize that three members of her own family had been subjected to compulsory accomodation in Rosenheimer Straße 40 and deported from there to Auschwitz: Else Simon (Claudia's great aunt), Helga Kaufmann (Claudia's aunt) and Yvonne Luise (Claudia's cousin). Since 2016 Marie Rolshoven has been honouring their memory in her apartment with documents from Berlin archives. It looked as if not another single photograph could be found. Up until now. Until Claudia Samter discovered us and opened her photograph album. Thank you Claudia for your trust.

Thank you Susana Fernández Molina. Without your article and your Citycize project, this would never have happened.

Claudia's mother, Ursula Samter née Kastan, was only a girl when she escaped with her scout group to Argentina in 1938. Claudia herself will come to Berlin in May to commemorate her lost relatives in the Rosenheimer Straße apartment and tell the daunting story of her mother's escape.

Ursula Kastan in front of her home on Krefelder Strasse in

Berlin-Moabit

(c)Claudia Samter, Buenos Aires

Frida Kastan née Stargardt and her sister Else Simon née Stargardt, with their daughters Ursula and Helga. (c) Claudia Samter, Buenos Aires